| ||||

| CANNONS OF THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO | ||||

| by | ||||

| Don Davie | ||||

The invention of gunpowder, a mixture of sulphur, charcoal and saltpetre commonly known today as black powder, has been ascribed variously to the Chinese, Indians, Arabs, Greeks, Germans and English and remains the subject of debate. Black powder was possibly used in rockets in the 10th century and ‘fire arrows’ containing black powder and propelled like rockets were in military use in China by AD 1000. In cannons, black powder was used as a propellant from the early-14th century and the Chinese were among the earliest exponents of the science of gunnery. The fleet of a Ming Admiral and Grand Eunuch, Zheng He, is said to have collected sulphur from a volcano on Java for use in medicines, alchemy and the manufacture of black powder in the early years of the 15th century. In venturing onto the oceans of the world at the time of the third Ming emperor, Zhu Di (r.1403-1424), Chinese mariners and traders sailed in enormous junks armed with cannons and far exceeding in size contemporary vessels of the West. Passage to Southeast Asia, Africa, Southwest Asia and South Asia was made through the waters of the South China Sea and it is likely that the Chinese would have introduced the peoples of the Malay Archipelago to the instruments and techniques of gunnery at that time. | ||||

It is clear that muzzle-loading cannons were a feature of the Malay armaments inventory prior to the advent of European expansion into Southeast Asia. European voyaging by sea to South Asia was initiated by the Portuguese when Vasco da Gama made the port of Calicut on India’s Malabar Coast in 1489. The Portuguese then sought to establish themselves in Southeast Asia. When Portuguese forces commanded by Alfonso de Albuquerque besieged Melaka in 1511, the Malays employed cannons in defence of the city and it is said that 3000 pieces of artillery were captured when the defenders capitulated. The nature of the cannons used by the Malays at Melaka is not known but it has been noted that they were outranged by the Portuguese guns and it is probable that they were of small calibre. After Ferdinand Magellan’s death in the Philippine Islands in 1521, the survivors of his expedition found cannons in use in the East Indies as they made their return westward to Europe. | ||||

Wheeled artillery was not a significant feature of warlike operations in maritime Southeast Asia in pre-colonial times but swivel guns for use on land or at sea proliferated. Known as lela ormeriam kecil (small cannon) in Malay, or as lantaka in the region of the southern Philippines under Malay influence, these pieces were perhaps copied from the small guns on yokes or swivels developed in Europe for placement on the bulwarks of naval and merchant vessels. While the European guns may have been brought to the Malay lands by Arab traders, Malay cannons (meriam) of local origin were commonly of a dissimilar construction to European weapons of the same period. | ||||

Generally, meriam kecil did not follow the design of European cannons comprising - from the face - muzzle, chase, second reinforce, first reinforce and cascabel. In lieu of the cascabel button, meriam kecil normally had a tubular projection capable of accepting a tiller, perhaps the butt of the rammer, as an aid to laying– elevating, depressing and traversing – the piece. A variant of the meriam kecil had a curved metal handle (monkey tail) for laying rather than the socket and tiller arrangement. They did have trunnions, situated a little below the centreline of the bore as was the | ||||

| ||||

Malay meriam of all sizes were often highly decorated with scrollwork, floral and geometric designs, bands and rings. Barrels were usually slim, tapered and round, although octagonal and half-octagonal barrels were not rare, and there were fluted barrels, some with spiral fluting. Customarily, muzzles were expanded in a conical or discoidal form but were sometimes cast to represent a dragon’s mouth. Crude open sights, a blade or square knob at the muzzle and two projecting ears or an oval bulge in the vicinity of the vent, were usually provided. Even the common pieces usually had some form of decoration. | ||||

| ||||

Meriam kecil were employed by the many pirates who preyed upon commerce between the hundreds of islands of the archipelago and by trading vessels as a defence against piracy. Thesultans and rajas of the region installed cannons in the forts erected for the protection of their ports and communities and for the control of riverine commerce. From at least the 16th century, it was common for Malay sailing vessels, perahu, on inter-island trade to carry a number of meriam kecil of small to moderate size. Typically, bore diameters were in the range of about 10 millimetres to 50 millimetres and lengths varied from about 800 millimetres to 1600 millimetres. | ||||

The founding of cannons was undertaken in the Malay lands at an early time. Foundries located in Brunei, Trengganu on the Malay Peninsula, Palembang in South Sumatra, the Minangkabau region of West Sumatra and Aceh in the north of that island cast cannons in brass, bronze and, less commonly, iron. It has been reported that some cannons of the Malay pattern were cast by the Dutch, both in the East Indies and in the Netherlands, and by the Portuguese at Macau during colonial times. | ||||

Turkish artisans skilled in the casting of cannons came to Aceh after the sultan sent an embassy to Turkey in the mid-17th century. Following a visit to Banda Aceh in the course of a voyage to the East Indies in the vessel Cygnet in 1687, the English seaman and buccaneer William Dampier commented that the ruler’s palace had about it ‘some great guns’. Four were of brass and were said to have been a gift from the English king James I (r.1603-1625). | ||||

In common with European muzzle-loading ordnance, the basic design of the Malay cannons changed little over the centuries and the muzzle-loading meriam remained in service until comparatively modern times. The European presence in the region brought a measure of political and social stability in the late-19th century. This was reinforced by the suppression of the most rampant forms of piracy by the British Royal Navy and the Netherlands Koninklijike Marine and brought a decline in the prevalence of cannons. At that time also, the possession of firearms of all types, except by Europeans, was very much circumscribed by the British and Dutch wherever they had established their colonial authority in the archipelago. Nevertheless, firearms and cannons remained in large numbers in the peripheral areas of the Outer Islands of the East Indies where Dutch dominion did not prevail or was at best tenuous. | ||||

The noted writer Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) served for some time in Southeast Asian waters as a deck officer and master mariner in the British Mercantile Marine and was familiar with the Malay Archipelago as it was in the closing decades of the 19th century. In his fictional workLord Jim, he placed much of his story in the domain of a minor raja in an outlying region of the archipelago. He wrote of a kampung of Bugis immigrants from Sulawesi being defended by ‘two rusty 7-pounders, a lot of small brass cannon – currency cannon.’ Conrad gave an accurate representation of the times and conditions of which he wrote and his comment is indicative of the ubiquitous presence of cannons in the outer reaches of the archipelago. Alfred Searcy, who was Sub-Collector of Customs for the Colony of South Australia in Darwin from 1882 to 1896, commented that the perahu of the Makassan trepangers working on the North Australian coast during his time in Darwin were all armed with ‘numbers of very ancient cannon.’ | ||||

| ||||

button but lacking a yoke, carriage or handle. While one source has it that pistols were rare in the region until quite recent times and that the miniatures were carried in a waist band or sash and used as hand guns, they would have been particularly inconvenient in this application. Perhaps, they were used to fire salutes or were produced as a novelty. In any case, they were still to be found in Indonesia in some quantity in the late-20th century. | ||||

In a region with a mainly barter economy and limited reserves of currency, meriam kecilsometimes served as currency. The value of a piece is stated to have been determined by the nature and mass of the metal from which it was cast and could perhaps have been increased by the intricacy of its embellishment. Meriam kecil were sometimes displayed ostentatiously outside residences as an indication of wealth. While serving in HMAS Geelong in 1993, Craig Wharton of ACANT saw in Ujung Pandang (formerly Makassar) in South Sulawesi a row ofmeriam kecil embedded in the ground with their muzzles uppermost to form an ornamental fence. A sad end for examples of the craftsmanship of the past but it would appear that, at that time at least, they were not seen as rarities of any monetary or cultural worth. | ||||

With animistic beliefs still prevailing in the region despite the coming of Islam and Christianity,meriam were often credited with having supernatural powers, particularly as aids to fertility. | ||||

A large British cannon is displayed on the broad flight of steps leading to the entrance of the building housing the office of the governor of the province of Nusa Tenggara Timur on Jalan Raya El Tari in Kupang. Mounted on an iron carriage, the piece is embossed with the cipher GR. As the cipher does not include a number, it is presumably that of King George I (r.1714-1727). The Indonesian authorities were ignorant of the history of the piece. The British occupied Kupang from 1812 to 1816 and it is possibly a relic of the British interregnum in the Netherlands East Indies during the Napoleonic Wars. | ||||

| ||||

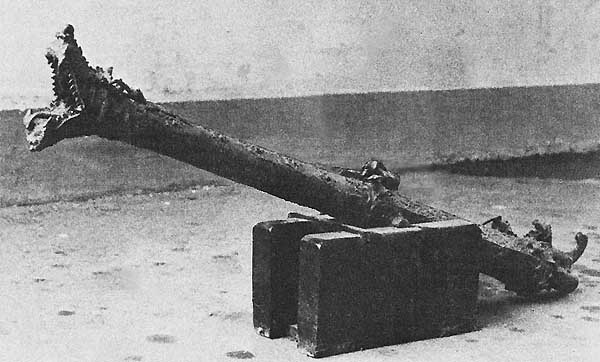

Other European and indigenous cannon would still exist in the archipelago as remnants of past confrontations and disasters. In particular, it is likely that there are many cannons in the more remote areas as the loss of European and local shipping in the time of armed sailing vessels, due to adverse weather, navigational errors or attack, was quite common. As an example, HM colonial brig Lady Nelson and the schooner Stedcombe failed to return to Fort Dundas on Melville Island after voyaging to South Maluku in 1825. In the course of a search for relics ofLady Nelson and Stedcombe, Peter Spillet of Darwin in 1981 saw and photographed in the region cannons believed to be from the lost vessels. One was an unmarked iron piece with a length of 1700 millimetres and a bore of 89 millimetres and thought to be from Stedcombe. The other was an iron carronade marked with the numerals 6-1-7 and the broad arrow indicating government property and was said to be from Lady Nelson. This piece had a length of about 1240 millimetres and a bore of 156 millimetres. | ||||

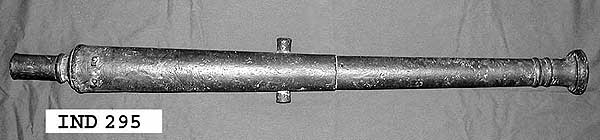

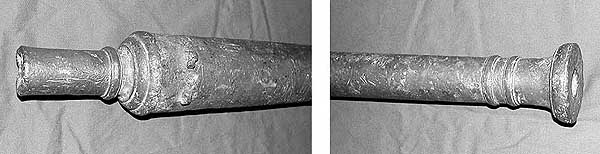

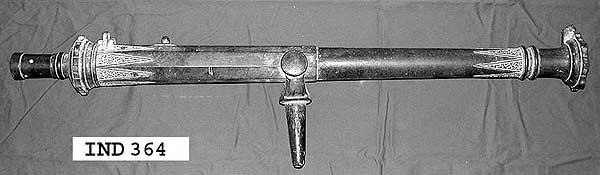

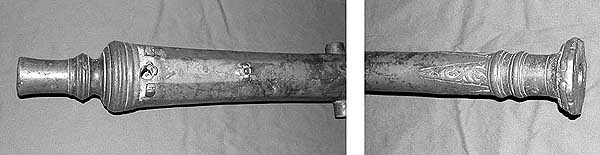

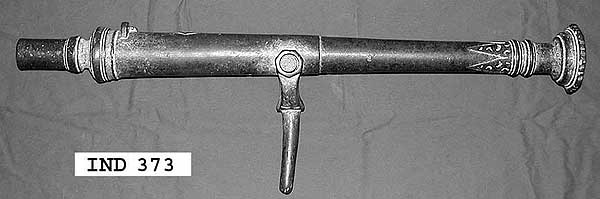

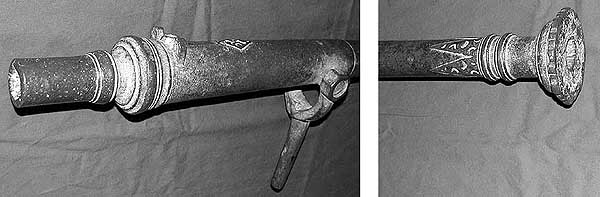

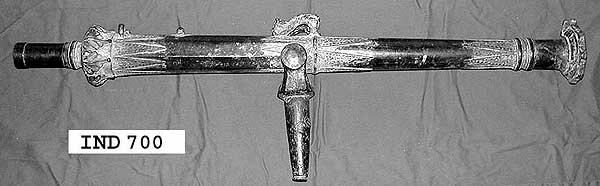

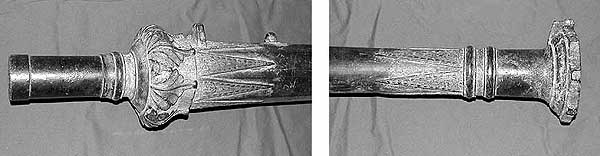

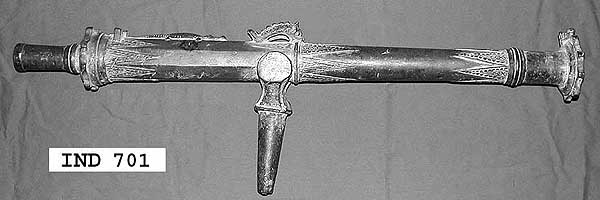

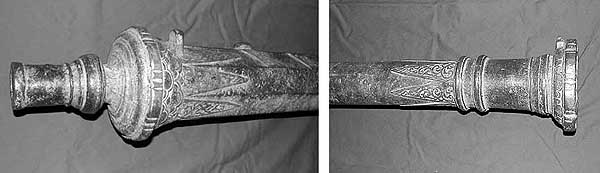

The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) located at Darwin’s Bullocky Point has seven meriam kecil in its Southeast Asian collection. These relatively plain pieces, illustrated below, are typical of the everyday armament that would have been mounted in perahu used in trade, war or piracy and in defensive positions on land. Calibres are nominal and the bores display a tendency to deviate from strict circularity! Length overall is from the muzzle to the rear of the tubular laying projection. All were cast from brass or bronze. The IND numbers are MAGNT collection numbers. | ||||

IND 295: loa 1020 mm, calibre 27 mm. Barrel round and plain. Some damage to the laying projection. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| IND 364: loa 1220 mm, calibre 30 mm. Barrel octagonal to trunnions then round. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| IND 371: loa 880mm, calibre 22mm. Barrel round. Yoke missing. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| IND 373: loa 770 mm, calibre 25 mm. Barrel round. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| IND 700: loa 1180 mm, calibre 35 mm, barrel octagonal to trunnions then round. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

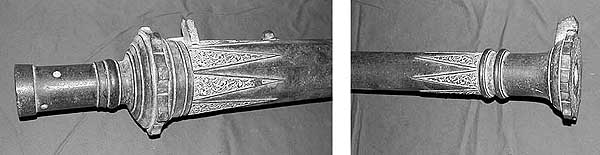

IND 701: loa 780 mm, calibre 26 mm, barrel octagonal to trunnions then round. The flat ahead of the vent bears a very neat representation of a crocodile. Twin ‘handles’ in the form of dolphins. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

IND 1515: loa 1480 mm, calibre 37 mm, barrel octagonal to trunnions then round. Elaborately decorated and twin ‘handles’ in the form of dolphins. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

Almost unceasing warfare between the states of the Malay Archipelago, endemic piracy and resistance to European colonialism all promoted a requirement for cannons of European and local design for either aggression or protection. Cannons were particularly common at sea and the meriam kecil are among the most unusual and interesting of the artefacts of the Malay Archipelago. | ||||

The cannons in the MAGNT collection were examined and photographed with the kind permission of Anna Malgorzewicz, Director MAGNT, and the most obliging assistance of Malene Bjornskov, Collections Manager. | ||||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | ||||

| Conrad, J., Lord Jim, New York, Everyman’s Library-Alfred A. Knopf, 1992. | ||||

Downey, F., ‘The Rockets Red Glare’, Gun Digest, 26th Edition, Chicago, Follett Publishing Company, 1972. | ||||

Harding, D. (ed.), Weapons: an international encyclopedia from 5000BC to 2000AD, London, Book Club Associates, 1980. | ||||

| Menzies, G,. 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, London, Bantam Press, 2002. | ||||

| Munday, J., Naval Cannon, Princes Risborough, Shire Publications Ltd. 1998. | ||||

| Peterson, H.L., The Book of the Gun, London, Paul Hamlyn, 1963. | ||||

| Pope, D., Guns, London, George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Limited, 1972. | ||||

Sanders, J.W., ‘Swivel Guns of Southeast Asia’, Gun Digest, 36th Edition, Northfield, DBI Books, Inc., 1982. | ||||

Searcy, A., In Australian Tropics, (2nd Edition)(Facsimile Edition), Carlisle, Hesperian Press, 1984 (1909). | ||||

Spillet, P., The Discovery of the Relics of H.M. Colonial Brig Lady Nelson and the Schooner Stedcombe, Darwin, Historical Society of the Northern Territory, 1982. | ||||

| Turnbull, C.M., A History of Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1989. | ||||

| Viviano, F., ‘China’s Great Armada’, National Geographic, Vol. 208, No. 1, July 2005. | ||||

| Winstedt, R., Malaya and Its History, London, Hutchinson University Library, 1966. | ||||

Zainu’ddin, A.G., A Short History of Indonesia (2nd Edition), Melbourne, Cassell Australia, 1980. Dipetik dari http://www.acant.org.au/Articles/MalayCannons.html |

"Jika mahu membunuh tanaman, racunlah akarnya, jika mahu membunuh bangsa, racunlah sejarah mereka"

Jumaat, 30 September 2011

CANNONS OF THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO

Langgan:

Ulasan (Atom)